I have received comments from people thinking that I am socialist due to my criticisms of the capitalism system (or rather liberal neo-capitalism).

Those who have been following me for a long time already know that I am actually a monarchist and briefly exposed some arguments in favor of this regime in the article below.

Hail to the Monarchy—Dupont Lajoie—The angry French man (substack.com)

Regardless, in our polarized world, if you criticize capitalism, you are quickly labeled socialist or communist, and if you criticize socialism, you will be called a capitalist—you are compelled to pick between one of these two economic models.

However, there are alternatives to those ideologies that place class conflict at the heart of their doctrines. Corporatism for instance promote the cooperation between the classes, the organization of society into specialized groups and the collaboration between those groups. Corporatism advocate for a society not stratified in upper and lower classes but in functional classes based on skills and occupation.

Unlike socialism in which the means of production are managed by the political leaders of the community, and capitalism in which the means of production are managed by the richest, corporatism propose that the workers manage the means of production. In short, corporatism promote a world in which the economy is run by family businesses, craftsmen, small producers…

This ideology is not to be confused with corporatocracy i.e. a system in which a government is controlled by large companies or group of companies (For instance “The East India Company”, a trading company gaining responsibility of substantial parts of India [1600–1878] or “The Congo Free State” privately owned by King Leopold [1885–1908]) or corporate interests (the USA under the gilded age [1870–1890]).

A corporatocracy is a regime in which the interests of private companies financing the government surpass the interests of the common people. Oppositely, corporatism is the organization of the trade by the men of the trade and therefore rejects privatization and the orientation of production exclusively towards profit.

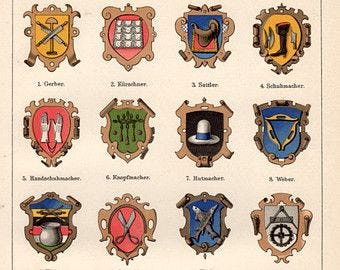

Corporatism is also different from the numerous state-owned corporate trials of the 20th century totalitarian regime (Hitler, Mussolini, Salazar). Rather than the authority integrating every single corporate interests, corporatism, as it was practiced in medieval France, was the organization of the trades in free, decentralized, autonomous bodies or guilds self-directed by tradesmen. The monarchy was only intervening to prevent excessive abuses.

Corporations emerged in the 12th century in France when craftsmen from the same trade voluntarily joined forces to defend their interests. They were an organization of labor which guarantees the freedom of the workers.

Little by little, those guilds were recognized by the lords and then by the king himself. They were governed by an ordinance that was rudimentary at first before becoming more evolved with time. As such, in 1268, Étienne Boileau, Provost of Paris, detailed in “The Book of Crafts” (Le Livre des Métiers) the customs and regulations of all the Parisian trades. Boileau described the provisions of the labors legislations which will last until the dissolution of the corporations.

Therefore, the corporations were not the creation of the monarchy but the creation of tradesmen. The monarchy (and the church) only ensured that corporate privileges would not end up being detrimental to the national common good. Although corporations were subjected to the moral control of the monarchy, they remained institutions of freedom founded on the principle of election and self-management.

In the Middle Ages, one had to join a corporation in order to practice a trade. Workers first start as apprentices and trained over several years with a master. They had as many rights as they had duties. In addition to receiving an instruction, apprentices were housed, fed and clothed by the master. They were treated like a member of the family. Entering a corporation was first and foremost becoming part of a fraternal community.

At the end of the apprenticeship period, workers were promoted to the status of “compagnon” (valet). Some would be hired by their master for a year, renewable if both parties agree. Others would embark on a “tour of France”, finding work from one town to another in order to perfect their technique and skills, gain experience, discover new knowledges and ultimately receive the position of master.

In any case, valets would never remain unemployed, the corporation always provide work for its members.

To become a master, valets needed to pass an examination, stand in front of a jury and produce a “masterpiece” i.e. a proof of their talent and highly professional value. Although at this time in France, no one could set up shop and sell a commodity without belonging to the corporation and acquiring the status of master, only a minority of valets were failing the test.

The newly appointed masters had to take an oath on the saint’s relics or gospels then pay the rights of mastery before being able to open their business.

The workers were protected by the Christian moral order as well as the legislative texts of the corporation. Each year, apprentices, valets and masters would elect jurors whose main missions were to resolve conflicts between employers and workers, prevent unfair dismissals, ensure payment of a fair salary and reasonable working hours. They frequently visited workshops and punish fraud. Above all, they were appointed to defend the rights and privileges of the corporation they represented.

In corporations, the common interest prevails in order to secure the safeguard and longevity of the trade. The production was proportionate to the needs, the quality of the products and fair price were guaranteed, the relationship with other trades were delineated.

Each corporation had its own laws, rites, religious festivals, holidays and processions. Each defined the attributes of mastership, its guideline (working hours, salary, etc.), regulated the conditions of competition (price, quality), controlled and limited foreign labor (thus preventing social dumping).

Corporations were autonomous and fraternal organizations. They ensured the social cohesion between members and managed a common patrimony. They had their own social security, their own forms of pensions funded by the membership fees.

They assumed the material and moral assistance of the poor, sick, elderly, widowed or orphaned… . Unemployed workers were taken care of until they find a new job suiting their qualifications and knowledge. And a master’s wife would inherit of her husband title in case of his premature death so she could continue running the business.

The corporations restored autonomy and empowered workers in their profession by making them owners of their trade. They allowed for social mobility through work: workers started as apprentices and ended up being masters.

The revolution would mark the demise of the corporations. French economist such as François Quesnay, seduced by the Anglo-Saxons’ theories of economic liberalism, called for constitutional limits on the power of the monarch. Similarly to the British Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the American Revolution of 1776, the French Revolution of 1789 advanced economic liberalism in the name of individual freedom.

On June 1791, the Le Chapelier Law (Loi Le Chapelier) was passed, prohibiting tradesmen to associate with a view to forming regulations on their common interest. Perhaps the corporations were targeted for their reject of economic liberalism (the free movement of grain, low prices…), or perhaps we reproached them to have created their own banks independently to the state and financial lobbies, ensuring a patrimony to each individual, or perhaps the bourgeoisie who had just taken over the power forbade any principle of association in order to dominate the working class.

While the corporations had subjected trades to the moral authority of the monarchy and the church, the revolution had destroyed the latest institutions of regulation protecting workers against the violence of economic liberalism. The proletariat would soon realize that exploitation came hidden behind the ideals of freedom.

Without any intermediary body, individuals sought to pursue their own interest rather than a common good and workers no longer answered to a moral imperative from the trade (i.e. the community) but submitted to the law of the market.

The bourgeoisie imposed a model in which money replaced hard work as the new criterion of selection. No need to become a master, just having enough funds to pay rent, workers, materials … suffice to open a business. The French Revolution had transformed a moral economy into a market economy.

In the 19th, the working class was then plunged into the brutality of the Industrial Revolution and the bloody and excessive repressions of the bourgeois republic. They experienced falling wages, scarcity, unemployment, and rising prices. Strikes were severely reprimanded.

With the end of corporations, the principle of opposition has replaced the principle of union and organization. And with globalization, multinational companies offering standardized products have replaced the local economies which reflected what the French call “terroir” i.e. a unique art of living anchored in a specific land.

The beauty of particular artisanal modes of production slowly disappeared to make space for the uniform ugliness of the postmodern world.

Nowadays, only a monarchy could bring back true corporatism. Indeed, not only the corporations were established, endured and prospered under the monarchy but only a form of government that hold in its core the principle of subsidiarity can ensure the autonomy of the workers.

A decentralized monarchy offers regional, provincial, and individual freedom. Moreover, it rids the elections of the parasitism of the parties. Similarly, corporatism is by definition a decentralization of the authority and is therefore incompatible with the republican logic centralizing power.

The corporations provide insurance and assistance to their members, they allow citizens not to be indebted to the government. Obviously, corporatism is not an ideal system, but it promotes freedoms, common good individual fulfillment and turn workers into connoisseur, professional, owner of their trade.

Corporatism support the monarchy distancing itself from absolutism and parliamentarism. The king himself is a connoisseur, a professional, owner of his trade who learn from a young age everything he needs to know to reign and consequently is better suited to govern than any politicians or parties in the republican system. And with the principle of dynastic heredity, his particular interests merge with that of the community.

Corporations are natural organic groups that put honor in labor and allow workers to own their trade. While capitalism values free market and entrepreneurship and socialism praise planned economy and social welfare programs, corporatism imposes itself against the social harms generated by economic liberalism and the totalitarian stranglehold of the state inherent of collectivist regimes.